Vitaly and the Price of “Money Talks”

Seeds of Fire Current Events-Special Reports

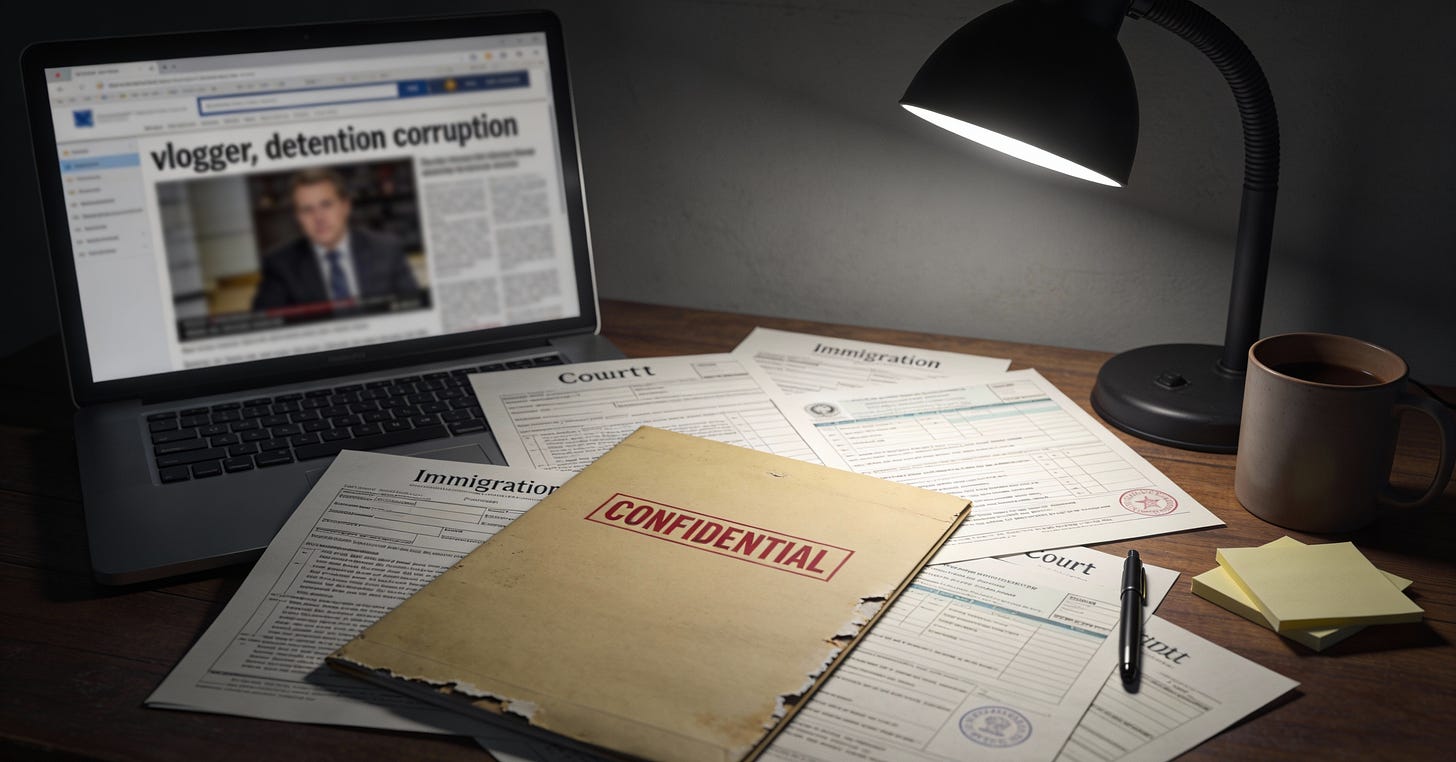

A Seeds of Fire special investigation by The Vault Investigates.

This Live Case grows straight out of “BILLIONS STOLEN WHILE THEY DROWN,” where we followed how flood‑control money vanished while Filipinos were left to sink in preventable floods. Today’s episode tracks what happens next: how a foreign vlogger tries to turn that same system—Philippine detention and corruption—into rage‑bait content.

Dear Friends,

In collaboration with Anonymous Media Group and The Dirty Dozen Dispatch, we continue our Seeds of Fire series with a special report exposing how poverty, disaster, and digital systems are exploited in the Philippines.

Newly deported Russian vlogger Vitaly Zdorovetskiy is back in a safe studio, bragging that he had a secret phone “the whole time in jail” in the Philippines and promising to “expose corruption” for views. On Adin Ross’ stream and other platforms, he laughs about how “money talks in the Philippines” and how easy it supposedly was to film content from inside detention.

On Filipino feeds, the clip landed like salt on an open wound. People shared reactions that ranged from “matagal na naming alam ’yan” to anger that a foreign influencer can turn alleged bribery into a punchline while Filipino detainees and families live with the consequences every day.

The Livestream That Turned a Jail into Content

In the stream, Vitaly sells a familiar storyline: he was locked up in a dangerous Philippine jail, he outsmarted the system, he secretly recorded everything, and now he will return as the brave narrator who “barely survived” to tell the tale. He hints at guards taking cash, special treatment, and the promise of a massive “exposé” video that will finally reveal how corrupt the country is.

It is classic rage‑bait and poverty‑porn structure. A foreign protagonist, a “crazy” Third World setting, local workers and detainees reduced to background characters, and a promise that all of this chaos will soon be uploaded in a monetized series. The risk is that once again, the Philippines is framed not as a place full of human beings with rights but as a dangerous theme park for other people’s brand redemption arcs.

What Vitaly Claims on Adin Ross’ Show

Across clips and write‑ups, his key claims are simple and explosive:

that he had a phone the entire time he was detained in a Philippine facility and was able to vlog freely;

that “money talks” and that bribing or paying guards was easy;

that he will now expose everything in a documentary‑style release.

Entertainment outlets outside the Philippines have amplified these quotes, framing the Philippine detention system as a place where anything can be bought if you have enough cash and followers. What gets lost is that if any of this is true, it is not a quirky content hook—it is evidence of a serious breakdown in detention security, fairness, and accountability, with direct consequences for Filipinos and other foreign detainees who do not have a YouTube empire to fall back on.

What BI and DILG Say Back

Philippine authorities have not taken his boasting at face value. The Bureau of Immigration (BI) has publicly dismissed much of his narrative as self‑serving “rage‑bait” designed to make income abroad, even as it confirms that internal investigations are underway. Reports indicate that multiple BI personnel, including a warden, have resigned or been sacked over alleged favors and possible access to gadgets and filming while he was detained.

Officials have warned that if he can prove he bribed guards or other personnel to obtain contraband phones and privileges, that could support administrative and even criminal cases against those involved. The message from government spokespeople is blunt: they see him as a deported alien now trying to profit from Philippine detention while the system absorbs the blowback. That does not erase real corruption—it just means the narrative battle has begun.

Phones, Favors, and Life Inside Detention

To understand why this matters for Filipinos, you have to look past the stream and into the cells. The Philippines has long struggled with overcrowded and under‑resourced detention facilities, from regular jails under the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) to specialized centers like the Bicutan Immigration Detention Center. International and local reports describe cramped conditions, limited health services, and slow case processing that can leave detainees—Filipino and foreign—waiting months or years for resolution.

In that environment, “special treatment” is not just a meme; it is a survival economy. Access to phones, cleaner space, better food, or faster paperwork often flows through informal payments, connections, or fear. When a foreign vlogger brags that he paid his way to a phone and content inside detention, he is not just clowning on the system—he is confirming what many families already suspect: that those without money or foreign passports live a different jail than those with both.

When Foreigners Sell “Philippines Is Corrupt” as a Brand

There is a deeper pattern here. Poverty‑porn and rage‑bait content about the Philippines often follows three moves:

Center a foreign narrator who discovers how “crazy” or “corrupt” the country is.

Turn ordinary Filipino hardship—poverty, overcrowding, bureaucratic cruelty—into cinematic plot twists.

Offer no space for Filipinos themselves to document, litigate, or define their own stories.

Vitaly did not arrive as a human‑rights observer or a jail‑reform advocate. He arrived as a prank and shock‑content creator whose previous work involved harassing people in public and pushing boundaries for clicks. Now that he has been deported, he is rebranding himself as a corruption whistleblower, with Philippine detention as his dark origin story. The danger is that his “exposé” will once again monetize Filipino suffering and institutional failure without any of the obligations that real whistleblowers and investigators accept.

If he truly has evidence—messages, payments, footage, or documents—of bribery, smuggling, or abuse in detention, that evidence belongs in Philippine court records, internal affairs files, and independent investigations, not just in a monetized, rage‑bait series published from the safety of another country.

Receipts: Documents and Timelines

What we know from public records and serious reporting so far:

Vitaly was arrested in the Philippines after a livestreamed stunt and later detained at a BI facility while facing cases related to his behavior and immigration status.

He was eventually deported and placed on the BI blacklist, meaning he is barred from returning to the Philippines.

Following the release of his claims about bribery and secret vlogging, BI and oversight bodies opened probes, and several personnel, including at least one warden, have resigned or been dismissed over alleged special favors.

Philippine officials have publicly challenged his narrative, calling it an attempt to profit by portraying the Philippines as irredeemably corrupt while investigations into actual misconduct move forward.

This is not the final record. It is the starting evidence map for a deeper, Filipino‑centered investigation of what really happens inside detention—who pays, who benefits, and who cannot turn their experience into content.

Call for Documents from Filipinos Who Lived This

If you are a current or former BI/BJMP staff member, a contractor, a lawyer, a detainee, or a family member who has seen phones, favors, and “special treatment” inside Philippine detention, this is your lane. This work needs your receipts.

We are looking for:

Commitment orders, booking sheets, visitor logs, and internal incident reports that show patterns in who gets what treatment.

Internal memos, chat logs, or emails about phones, gadgets, and unauthorized filming inside detention facilities.

Court filings, Ombudsman or CHR complaints, or administrative cases that touch on bribery, extortion, or preferential treatment in detention.

Before you send anything, please read the Policies and Source Protection page linked from The Vault Investigates and TruthDrop.io. It explains how tips are handled, how documents are stored, and what options you have for anonymity, delayed publication, or joint work with other reporters.

Vitaly has already turned Philippine detention into content. The question now is whether Filipinos most affected by that system—and those who have worked inside it—will have the chance to turn their documents, not just their pain, into power.

Keep Seeds of Fire Burning

Seeds of Fire and The Vault Investigates are independent and reader‑funded. No sponsors, no protection rackets—just slow, document‑heavy reporting on the business of poverty and the people who profit from it.

If this Live Case helped you see the “content” differently, you can:

Ko‑fi – small monthly help. Think of it as buying this project one coffee a month so the lights and servers stay on.

→ Ko-fi Small Monthly

PayPal – once‑a‑year boost. If you’d rather do it once and be done, you can drop a yearly gift here that helps cover hosting and investigation tools.

→ PayPal One and Done

– Share this piece with one person who needs to understand how our pain is being turned into someone else’s brand.Most reporting here will stay free for Filipinos, Puerto Ricans, and working‑class readers. If you can afford to give, your support keeps the gates open for those who can’t.

#Seeds of Fire #Investigative Journalism #Poverty Porn #Digital Exploitation #Business of Poverty # Philippines #Corruption #Social Media Accountability #Creator Economy